Nikki Brown has provided a thought-provoking post on analysis. Many one-namers love the analysis phase of a study but are unsure how to start. It may vary depending on your study. For example, my one name study has very little UK content but is more a story of emigration from the Channel Islands to different parts of the world - i love to compare the lives/experiences of these emigrants depending on where they landed. NOTE: this was a technical challenge for poor Blogger due to the charts etc. and may appear a bit odd - if it is unreadable please provide a comment.

There has been a wide variety of blog posts on the Ruby website. They have inclluded origins and migrations of Rubys; name changes and confusions; discovering different records with new ways to use them, and problems when using them; persons of interest and of course, experiences and lessons (ususally good!) learnt from working in a team. I wondered if there was something new to do. I decided to examine the occupations of English Rubys recorded in the 1881 Census of england and Wales.

I

have ended up with a collection of figures and graphs but, to be honest, not

much of a conclusion. Perhaps, readers can draw their own or maybe the figures

themselves are of enough interest? I have taken suggestions of how this

information could be developed and at the end of the figures, I have highlighted

some of the problems of carrying forward the ideas, although this is mainly the

usual problem of not having enough time.

The

Figures

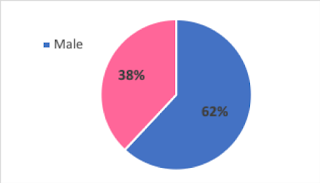

The total number of people with the surname Ruby on the England and Wales census was 231.

Total of all people on this census was 25, 974, 439. Therefore, Rubys comprised 0.000889 % of the population.

49% of them were in employment which was slightly higher than the general population in which 43 % were employed.

Total of all people on this census was 25, 974, 439. Therefore, Rubys comprised 0.000889 % of the population.

49% of them were in employment which was slightly higher than the general population in which 43 % were employed.

|

|

|

Agriculture

|

Food Industry

|

|

Total 11. All

male. Aged 15 to 70 years

|

Total 8 of

which there were 5 men and 3 women. Aged 16 – 71

|

|

The eldest is a

farmer of 30 acres, hay dealer and employer of 3 men.

Three are sons of the head of household. One is a hay dealer and the rest (6) are agricultural labourers |

2 Grocery

assistants (one male, one female), a grocer’s porter (male) and worker in the

grocery business (female), a fish porter, a journeyman baker, a milkman

(male) and a milk seller (female).

|

|

Note: the two

indoor farm servants have been counted as servants

|

|

|

|

Transport

|

|

Servants

|

Total 7, all

male. Aged 23 – 57 years

|

|

Total 23 of

which 4 were male and 19 female.

The 4 men included 2 indoor farm servants, a Page and "Boots (Inn Servant Domestics)" (the head was a hotel keeper). |

Four worked for the

Railway (a station master, signalman, guard and railway servant). The other 3

were a Millers Waggoner (Carman), Coachsmith and a Carman

|

|

The women were: 2

nurses, 3 cooks, 1 housemaid, 12 General domestic servants and a charwoman

(widowed)

|

|

|

Textiles

|

|

|

|

Some would be

factory and some in the home

|

|

Hospitality

Total 4. All female (although Ann recorded as male). Aged 16 – 71 years

A Licenced

Victualler, 2 barmaids (one described as a servant) and a widowed lodging

housekeeper

|

Total 16.

Aged 16 – 68 and there were 2 men and 14 women.

At least 3 of the women were widowed T

here was a dyer

(male), 2 cotton weavers (one male & one female), one corset maker, 8

dressmakers, one tailoress 2 laundresses and a rag sorter (widowed)

|

|

|

|

|

Building Trade

Total 11. All male Aged 15 – 56 years |

Factory workers

Total of 3, Aged 17 – 25 years. One male and two females. |

|

The eldest being a Builder

Employing 8 Men & 2 Boys Apprentices.

One carpenter, a painter, 5 bricklayers (one a journeyman), one Bricklayer's labourer, a Stone mason, and a Wall mason |

The male was

a key stamper and the women were a mantle maker and worker in a couch factory

|

|

|

|

|

|

Office workers

|

|

Other Trades

|

Total of 3,

all male, aged 24 – 58 years

|

|

Total 3, all

male. Aged 16 - 26

|

A Collector Taxes

(Clerk), Solicitors Clerk and a Journalist

|

|

A Blacksmith,

Padlock smith, and a gold beater

|

|

|

Emergency Services

|

|

|

Mines & Quarry

|

Total 3. All male.

Aged 24 - 45 years

|

|

Total of 7

men aged 13 - 52

|

Two police

constables and a fireman

|

|

1 tin miner, 2

Copper miners, 2 copper mine labourers, a coal trimmer and a quarry labourer

|

|

|

|

Armed Forces

|

|

Labourers and

General Labourers

|

Total of 5, all

male, aged 22 - 54 years

|

|

Total 8, all male.

Aged 16 – 71 years

|

Four in the Navy

and include a sailmaker

|

|

|

|

|

|

Entertainment

|

|

|

One 21-year-old

female musician

|

Any Conclusions?

The obvious thing to notice is the quite large

percentage, that is nearly a quarter, of Rubys in service. Apart from that, the

next biggest groups are in textiles, the building trade and farming. It is

quite an interesting mix. So how to make some sense of the figures?

a)

Comparing occupations to the

general population.

This proved more difficult than first thought.

Finding tables of occupations of the entire population on the 1881 census was

not difficult but interpreting them and comparing to my own was. Many sources

noted problems in compiling the tables in the first place, General Report/Section 8. VI Occupations. (http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/EW1881GEN/8) has figures that are too general or too detailed for comparison to the

above, as least without a considerable amount of further work

A vision of Britain through Time [1]

has looked closely at all aspects of the census and produced tabulated results.

Regarding the occupations on the 1881 census the site notes “The most

laborious, the most costly, and, after all, perhaps the least satisfactory part

of the Census, is that which is concerned with the occupations of the people”.

I wish I had read that before I started! The tables on this site

Other documents such as the 1998 study by Matthew Woollard, [2] notes problems with compiling the tables themselves because of “the number of the problems inherent in the collection of occupational titles” and “the problem of imperfection within the raw data.” As well as the definition of the term occupation at the time.

Other documents such as the 1998 study by Matthew Woollard, [2] notes problems with compiling the tables themselves because of “the number of the problems inherent in the collection of occupational titles” and “the problem of imperfection within the raw data.” As well as the definition of the term occupation at the time.

b)

Looking at changes in

occupation through time.

Inventions associated with the industrial

revolution meant that manufacturing replaced traditional rural lifestyles and

people migrated to cities to work in factories. Associated with this was also

the rise in industries to provide the workers with housing and railways to

transport the goods.

The occupations of the Rubys in 1881, however also shows the rise in domestic service as the Industrial revolution was also had an impact on women being employed outside the home [3].

The occupations of the Rubys in 1881, however also shows the rise in domestic service as the Industrial revolution was also had an impact on women being employed outside the home [3].

I was looking to compare the occupation figures

of the 1881 census and the 1841 census. The 1881 E&W census on the Ruby One

Drive matched the results when searching for Ruby on the 1881 census using

Family Search. However, I was unable to view the images to access the

occupations for the 1841 census from this site. (Although download is easier

than for other sites)

Although not as scientifically pleasing, I looked at using other commercial sites. However, as with my own study, I found another problem, in that numbers across sites do not match up. The same is true when searching for Ruby.

Although not as scientifically pleasing, I looked at using other commercial sites. However, as with my own study, I found another problem, in that numbers across sites do not match up. The same is true when searching for Ruby.

1841

Census

|

1881

Census

|

|

Family Search

|

140

|

231

|

Ancestry *

|

353

|

256

|

Find My Past

|

159

|

258

|

* (despite

an “exact search, some are not Ruby) ** (241 on a re-search)

It is possible to download from all sites and

compare the results for a more accurate dataset, but this takes a lot of time.

c) Another

thought is that the different occupations may well be area dependent. This of

course links into the industrial revolution too. But did the people move to the

jobs or did the jobs develop around them. For this to be answered fully would

require an analysis of the relationship between occupation and residence on the

1881 census and also a comparison of residence between the 1881 and earlier

censuses. I admit this is new to me as in my own study, the Pullum were all in

London (well also Surrey or Middlesex back then) by the 1841 census.

How to

proceed?

Apart for a lack of time, I am not sure which

comparisons would be the most enlightening and any of them would probably

expand beyond the size of a blog! Hopefully though there is some food for

thought here.

Sources

2. Woollard, Matthew. (1998).

The Classification of Occupations in the 1881 Census of England and Wales.

History and Computing. 10. 10.3366/hac.1998.10.1-3.17.

3. Burnette, Joyce. “Women

Workers in the British Industrial Revolution”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by

Robert Whaples. March 26, 2008. URL http://eh.net/encyclopedia/women-workers-in-the-british-industrial-revolution/

Comments

Post a Comment